Going into a UPEN meeting the next day seemed fitting considering the certain critical need for open and productive dialogue between HEIs and policymakers over the coming years, not just in the UK but globally.

The resounding message from the members meeting was one that speaks to the fundamental need for deeper, co-collaborative work and exchange to occur, not just between HEIs and policymakers, but between HEIs themselves. Perhaps innovation and excellence are two things more easily generated in a hive rather than the individual walking alone.

These are exciting times for UPEN. They are coming up to a pivot point for the organisation, exploring how it can work better with its members, and become a hub to support creative approaches to improving partnerships across the HEI and policy landscape. Co-collaboration is at the heart of this, and focuses on enhancing connections between academic research and public policymaking; elevating academic-policy engagement capacity and capability, and catalysing innovation and delivering system change.

Jonathan Breckon’s talk; ‘Growing a University Policy Function’, derived from the brilliant work undertaken at CAPE, also spoke to these aims and embedding collaborative work between HEIs and policymakers. While it may be tempting to take a siloed approach when building policy capacity within HEIs, to best overcome the dissonance echoed by Caplan’s ‘two communities’ commentary between researcher and policymaker, establishing a balanced two-way dialogue is key: evidence-informed policy sits at the intersection between expertise, strategy, and the core values of the policy function.

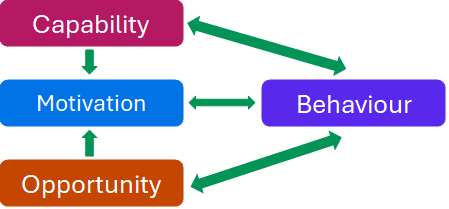

Breckon further highlighted the Com-B model as a useful methodology that has been successfully applied to the implementation of policy functions. Reflecting on Caplan’s paper, the Com-B model could address the issue of ‘separate worlds’ inhabited by the researcher and policymaker, mediating the ‘different and often conflicting values, different reward systems and different languages’ on either side (Caplan, 1979, p. 459). At its core, Com-B looks to first understand behaviour to recognise what can be done to change it.

Figure 1: The Com-B model

Capability (the psychological ability to enact behaviour) and opportunity (the physical and socio-environmental factors that enable behaviour) have potential to influence behaviour change through motivation (reflective and automatic mechanisms that inhibit or activate behaviour) but also have capacity to be influenced by the resultant change. The Com-B model provides a framework for social behaviour change for policymakers to create effective, lasting interventions. As researchers and HEIs, we can learn from this model when considering our engagement with the policy landscape, and how our research can drive opportunity, increase capability, and affect motivation of various groups. What I liked about this methodology is how its goal for proactive, evidence-based interventions required to affect behaviour demands communication and collaboration between all parties involved in the behaviour change process. Returning to Caplan’s two communities paper, the COM-B framework invites reciprocity and a pathway to improved knowledge utilisation in the policy landscape.

Improvement of knowledge utilisation within the policy landscape is the primary ambition of UPEN. Discussion in the afternoon fell around the underpinning pillars of this work, using the time to explore different pathways to maximise success. In the ‘Place’ group, the challenge of devolution and the question of how to engage across a range of local and combined authorities guided conversation. Suggestions included:

- Sharing knowledge and access points around government priorities

- Creating links between the various place-based research centres across the UK

- Utilising place as a tool for engagement

- Testing models of policy engagement in areas of specific and/or unique geographies

- Identify the lay of the land across place-based conversations – what has worked? What hasn’t worked? Why? Is there potential for scalability?

As demonstrated from the points above, building connections is entangled within the broader goal to generate capacity in relation to place-making policy initiatives. There are methodologies and frameworks out there that can support this drive, but most importantly, evident from the members meeting, there are lots of enthusiastic people within the sector with a wealth of expertise and experience willing to make change.

References:

Caplan, N., 1979, “The Two-Communities Theory and Knowledge Utilization: Is There Really a Gap? The Significance of the “Gap” Micro-Level Problems: Instrumental Utilization Meth-Level Problems: Conceptual Utilization Collaboration for Conceptual Utilization Conclusions Notes References”, The American Behavioral Scientist (pre-1986), vol. 22, no. 3, pp. 459.