From September 2021 – April 2022 we ran three funding calls for our CAPE Collaboration Fund, which awarded up to £25,000 for co-production projects between academics and policy partners. The fund was open to CAPE partner universities and each application needed a named policy partner. From 63 applications, we funded 20, committing over £400,000. The projects ranged from developing an integrated early care pathway for autistic children and families to delivering net zero retrofit for social housing in Camden, from improving school leader recruitment and retention to informing new anti-poverty strategies.

3 Funding Calls – 63 Applications – 20 successful projects

Funding for such projects, as far as we know, is quite uncommon in the sector. While all of our projects are ongoing (look out for forthcoming case studies) we explore the application process and what we think made a strong application and share our recommendations.

“I want to say a huge ‘thank you’ to the CAPE team for making funds available for staff time to work in these important policy engagements… it is rare to find this [type of funding], and this is a major stumbling block in being able to invest in relationships and activities of huge mutual benefit. Whether or not my funding is successful I wanted to recognise this and applaud it.”

CAPE Collaboration Fund applicant

What is a policy partner?

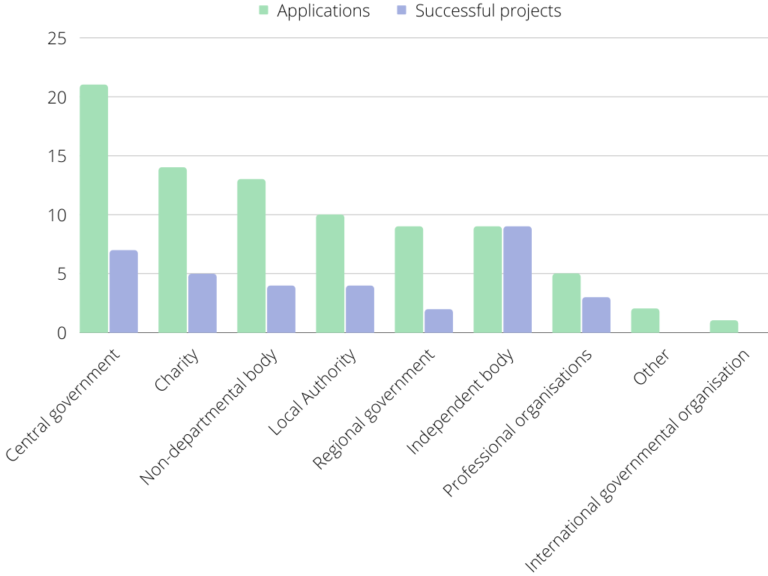

The definition of a ‘policy partner’ was kept intentionally broad – in the interest of not excluding innovative projects. Across the applications, we saw a huge diversity in the different organisations collaborating with our academics including central government departments, local authorities, professional bodies, charities and think tanks. This diversity was seen across both applications to the fund and across our successful projects.

What can co-production look like?

“The process of starting from questions asked by the policy partner, relating to topics about which they have a particular interest in having researched, seemed to work quite well as it meant that by definition the policy partner was invested in the project from the beginning, and is perhaps therefore a good example of “co-created” research.”

CAPE Collaboration Fund Principle Investigator

We also didn’t prescribe what co-production should look like in applications. As a result, the coproduced elements of the projects took many different forms – from academics being seconded into teams within policy partner organisations, to a policy partner placing a member of their team into a university research group. We saw applications that featured advisory boards and working groups involving researchers, policymakers and additional external contacts, to projects that involved weekly or monthly meetings between the partners to review progress. We saw a multitude of operational approaches to coproduction, with weekly and monthly meetings arranged between academic and policy contacts, the co-development of specific research questions and workshops, and various collaborative approaches to drafting policy orientated outputs such as briefing notes, toolkits and position papers.

We’ll be looking in more detail at what different types of co-production look like, whether there is a typology of coproduction in academic policy engagement over the coming months and we’d love to hear from anyone working in this space.

New relationships or old partnerships?

We were also interested to ascertain whether we funded applicants who (a) were “known” to policy engagement teams (or similar) at their universities or (b) had existing relationships with their policy partners. Essentially, were successful applications building new relationships or helping to strengthen existing connections?

Around half (32 of 63) of the applications were from researchers who didn’t appear to have an existing relationship with their university’s policy engagement unit or impact team. Similarly, around half of the policy partners (33 or 63) didn’t have existing connections with the PI’s university.

The picture however, changes significantly for our successful projects. Here, the majority of projects had pre-existing connections both with the university’s policy engagement team (or similar) and with the policy partner. This suggests the value of networks and building relationships. So, what was it about having pre-existing connections with policy partners which made those applications stronger?

“We knew enough about each other to trust that we were on the same page. There is mutual respect of each other’s expertise. We prioritised outputs for the partner before academic outputs.”

CAPE Collaboration Fund Principle Investigator

When analysing the articulation of policy demand within successful applications (which accounted for 25% of the application score), all applications presented at least one piece of evidence of policy demand for their proposed project. While some unsuccessful applications also presented clear evidence, we found many were lacking clear articulation of this. All of the 20 successful applications also clearly explained how their proposal linked with distinct priorities for the policy partners (such as Areas of Research Interest, or local authority strategies for example).

When talking about these relationships, one of our PIs noted that they had a productive but informal relationship with their policy partner and that the fund has incentivised them to move into a stronger and more formalised research partnership.

Your idea or mine?

We also asked successful PIs about where the idea for the project originated. The majority responded that the project was devised jointly by both the policy partner and the university (7 out of 12 responses) while a smaller number were projects originating from the academic themselves (4 out of 12 responses). Only one of the PIs who responded to the survey described the project as originating from the policy partner.

“It was really fortuitous- but perhaps that’s the point of good collaborations, they don’t always have to be “live” but can be ready to activate when needed/when opportunities arise.”

CAPE Collaboration Fund Principle Investigator

Our recommendations for successful co-production applications

So, what does all this mean if you’re putting together an application to fund a collaborative project with an element of policy engagement? Here are some take home messages.

- Co-production can take many forms. The most important thing is to be clear how this is happening all the way through the project, and how this links to the priorities of both partners.

- Develop relationships. Existing relationships were crucial for a strong application, and these projects often built of previous work between the researcher and policy partner.

- Articulate policy demand with your partner. Clearly link the project goals with existing priorities, strategies and other guidance so that the impact of the project is articulated.

Want to talk more about co-production? Get in touch

About CAPE

Capabilities in Academic Policy Engagement (CAPE) is a knowledge exchange and research project funded by Research England from 2020-2024, which has been exploring how to support effective and sustained engagement between academics and policy professionals. The project is a partnership between UCL and the Universities of Cambridge, Manchester, Northumbria and Nottingham in collaboration with the Government Office for Science, the Parliamentary Office for Science and Technology, Nesta and the Transforming Evidence Hub.

About CAPE blogs

CAPE blogs have been written by members of the CAPE team and policy partners reflecting on their learning and experience of academic policy engagement using practice-based evidence from the project.