Mobile Arts for Peace (MAP): Informing the National Curriculum and Youth Policy for Peacebuilding in Kyrgyzstan, Rwanda, Indonesia and Nepal (2020-2024) is an Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF) international project that provides a comparative approach on the use of interdisciplinary arts-based practices in collaboration with universities, cultural artists, civil society organisations, and young people across the world.

From the 22-26 May, MAP held the ‘Celebration’ International hybrid conference, including a series of panel discussions, policy dialogue sessions, ART-ing workshops, exhibitions, youth-led workshops, the launch of the Monitoring, Evaluation, and Learning (MEL) reports, reflection sessions, and a book launch. The conference spanning five countries, including the UK, provided comparative approaches and findings concerning how arts-based methods can address youth issues and influence policy and curriculum. Coinciding with UNESCO’s International Culture and Arts Education Week, the conference provided an opportunity to align the research project within the global agenda of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), and to explore and extend MAP futures.

The Policy Roundtable entitled ‘The MAP A/Effect: Informing Policy Engagement Processes & Outcomes with and through the Arts’ reflected upon how MAP projects sought to inform policy/curricula changes with and through particular art forms. Central to MAP’s applied research intentions, with policy engagement processes, is to value art forms for what they are, in and of themselves, but to also present art forms as living tools to innovate with/in/through policy engagement spaces. Policy engagement can be understood as both the outcomes and processes/methods (Wildervsky, 1979) towards seeking identified social change aims. In the case of arts-based approaches, this must also acknowledge the unpredictability of how these unfold. Dominant narratives of policy engagement often overly focus on outcomes alone, and can present policy goals as somewhat fixed/static. This session therefore opened up a space to reflect on the possibilities of arts-based approaches, and their contributions, including valuing the ‘making and creating’ and ‘a/effective processes’ through often nondiscursive forms towards policy influencing in local, national and international spaces.

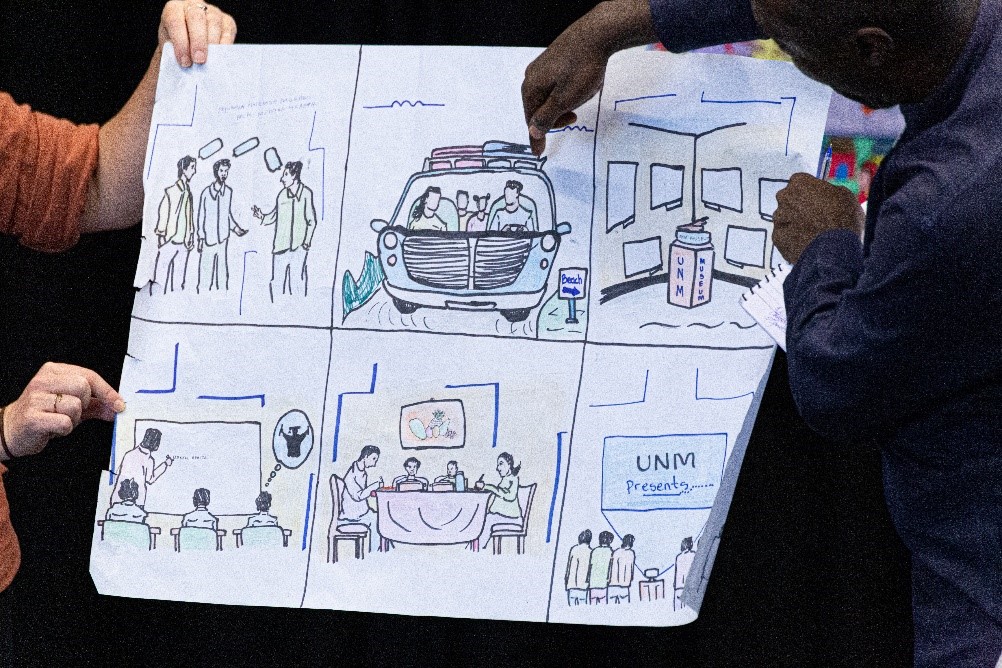

The core of the roundtable used a ‘Share & Respond’ dialogue format, pairing individuals with diverse perspectives on policy influencing. Contributors from MAP included a young researcher, Juhi Adhikari from Nepal, an NGO advocacy coordinator and researcher, Rendi Dinata from Save the Children International Indonesia, and from Dr. Chaste Uwihoreye, the Co-I of the MAP Rwanda projects. They each shared how particular art forms enabled developments concerning policy processes and/or outcomes through an object/artefact illustrating the presenter’s lived experiences, materially conveying ways of knowing that encouraged an open, collective and more than discursive (or often Western-orientated) reflection on policy engagement. Juhi referred to sanitary pads, Rendi to the musical bamboo instrument, the Angklung, and Chaste to a drawing (see the photo).

MAP Rwanda’s policy processes through a comic strip Credit: William Ball/MAP

Respondents from UNESCO and the International Advisory Board then reflected on these presentations through guiding questions. Michael Croft, the UNESCO representative to Nepal, commented that the focus should now be on finding the hook to advocate for Culture and Arts Education, in an overloaded curricula context where the “Ministry of Education has many requests for different types of curricula”. Wider discussions included acknowledging and valuing the creation and generation of ‘policy spaces’, and in this regard, I was reminded of Doreen Massey’s framing that ‘space’ is the product of relations and multiplicity; a condition for imagining futures that is not already foretold by the dominant temporal frames of modernism (i.e., progress, development, ‘the West’). In this regard space and art intersect. As the Minster for Education for Portugal, Dr João Costa at the UNESCO World Conference on Culture and Arts Education stated, “Art does not need justifying: it is the place of complexity, time, and deepness”. This is a crucial point for both policy-making (and art-making), both necessitate valuing empathetic and generative paradigms, which strive to make narrow, static viewpoints, such as populism intrinsically obsolete.

For further information: https://map.lincoln.ac.uk/

References

Werner M, Lave R, Christophers B, Peck J. (2018). Introduction: Spatializing Power: Doreen Massey on Space as Domination and Potential. In: Christophers B, Lave R, Peck J, Werner M, eds. The Doreen Massey Reader. Economic Transformations. Agenda Publishing; pp. 205-210.

Wildavsky, A. (1979). Speaking truth to power: The art and craft of policy analysis. Transaction Publishers.